Todd Melby: What's your favorite image from Killer of Sheep?

Charles Burnett: I do know one that disturbs me a lot.

Todd Melby: Okay. What?

Charles Burnett: Every time I see it, I cringe. There's a shot of these kids jumping [between] three story buildings, and you'll see it from the bottom up, looking up at these kids, flying over the rooftops and stuff. And it's a gap of like three or four feet between the next building, the jumping from one building to the next. At the time I was doing that, it never occurred to me what would happen to if those kids fell, you know? And the fact of the matter is they did it all the time. And that's where I got the idea to shoot it from because they were doing it. I just wanted to capture, but I shouldn't have done it. I shouldn't have allowed that to happen, you know. And I think about every time I see it. That would have been the end of them, you know. I know all sorts of things are still being going through this day. The repercussions of it. So that makes me cringe a bit when I when I see that scene. I showed you how you know, how how insensitive you can be when you're behind the camera, you allow anything to happen and you can, you know, stand back and look at at a distance even when it's happening. So, you know, you learn a lot about yourself. Look at some images. You know how how selfish you are, how selfish you can be. And so that's, you know, one of the concerns.

Todd Melby: It is a beautiful image, though. And it actually kind of reminds me of that Eugene Atget photo where somebody is kind of jumping over a bit of water someplace. And then I really like the image of the little girl in the dog mask, you know, because there's a scene with Stan. He's the protagonist of the story. Andhe's under the sink and he comes out and he's talking to a friend of his. And then suddenly his daughter shows up and she's probably five or six years old. And she's got this big dog mask on and you're like, wow.

Charles Burnett: Everything was storyboarded. And I remember having a mask a while before we shot, long before we shot that scene.

Todd Melby: Yeah, you know, it works. Yeah. Whatever reason you did it. It works and it's fantastic.

Charles Burnett: Well, look, the thing I have about that is I try to make everything as low key as possible to some extent without calling attention to it because you didn't want anything to be cute or anything like that. You want to be like this is know something that was there, like for example, like one of the issues I've always had with the film more than anything, was the whole title Killer of Sheep and the fact that the sheep in the film been slaughtered. And you wanted to not to make that connection symbolically about the slaughter and sheep and the people and all this kind of stuff. It's kind of, you know, fighting an uphill battle because people ask you what's the relation between the sheep and the people? The fact of the matter is, this guy works in this horrible job of killing sheep and the sheep is a placid. They just do whatever.

It's ironic because the Judas goat leads them up to the killing floor and they follow the duties go and then they're slaughtered. I got the idea from this. I was riding the bus one day and I met this young guy who was in work clothes and I was going to UCLA. And he was telling me he worked in a slaughterhouse. And what he did and how he did it. You're killing animals and sheep and stuff like that. At the time, they they used a sledgehammer on the cows. And so thought, ‘That's the kind of job my character needs to have in order to have these problems, you know, mental problems.’

That's where the idea of the sheep came from. It's to create these nightmares. Also the fact that it's a horrible job, but, you know, it's eating. I guess if if you're not a vegetarian, you could say, well, you know, it's a natural thing, you know, to some extent in order to survive and you need the protein, whatever it is. I don't know. But so it's just kind of reconcile that, you know, was one of the issues I was trying to bring out in the film as well, is that, you know, cruelty. You know, in order to survive, I guess you have to be cruel.

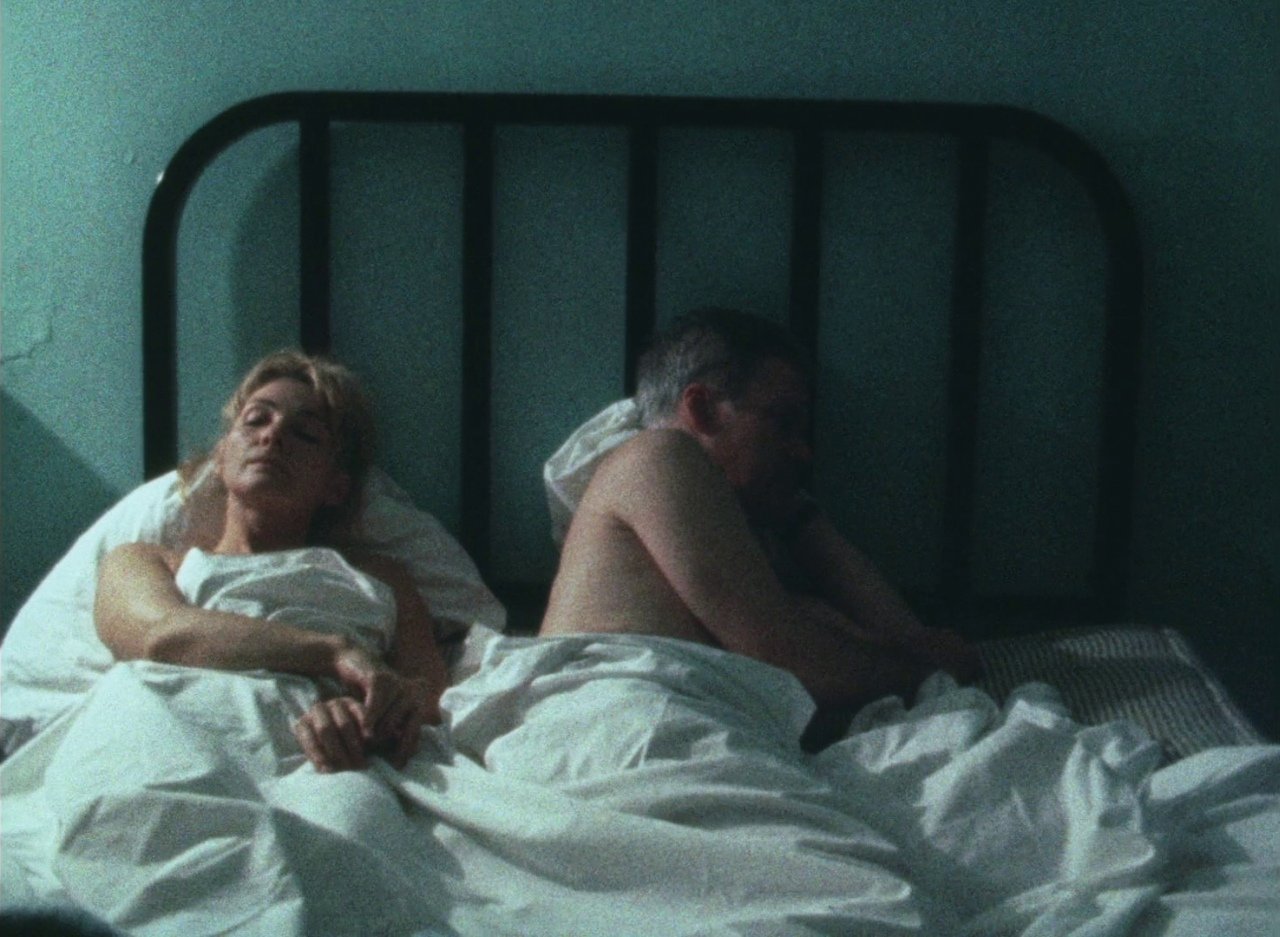

Todd Melby: It does help explain why Stan is so depressed.

Charles Burnett: When I was at his meat-packing place up in Vallejo, in northern California, cause you couldn't shoot in L.A. in any of those meatpacking places because the vegetarians got in getting in and started making these movies that were anti meat, you know, meat packing places and stuff like that. And so anyway, so I went in there and even a lot of the workers there and, you know, they would when they when they have a lunch break, you know, they'd wash your hands ago and bring out the sandwiches and and and whatever else and sit on a bench and start eating. I go out where there's a benches out and things like that and and leave these things hanging. You know, I didn't have lunch or anything those days I was there, you know, and I couldn't in fact. And when I when it was over, I became a temporary vegetarian. You know, I couldn't eat meat anymore for a while, but. Yeah, but those guys, you know, they're just they ring the bell, they go get their lunch budget hands and you'll get a lunch box and and go and sit out and miss it, you know. So. So I guess you could you see anything. Right. So. So I don't know. Stan was not. Apparently Stan wasn't that kind. And that certainly Stan goes kills animals to go and eat and forget about what he did. It sort of slowly worked, worked, worked out his nerve or whatever it is. So he was not that particular kind of a person.

Todd Melby: Yeah. There is one point in the film where he says, I'm working myself into my own hell. I can't get no sleep at night, no peace of mind. And then and then his friend Oscar, he says, ‘Why don't you kill yourself?’

Charles Burnett: Here is the thing about his gun and [taking] the easy way out. I mean, he's frustrated, everything like that. But his thing is partly that and trying to keep a sense of who he is.

Todd Melby: And other people can see it, too. They notice that he's down. Think they see that he's depressed. And at one point a couple of his so-called friends try to get him to help out out on a robbery.

Charles Burnett: He's upset because they look at him as depraved at a certain extent, you know, and are willing to do anything. I mean, he had opportunities to, you know, the lady at the store, at his liquor store who offered him a job. Is that, you know, you don’t really have to work that hard and you can come and be in the back with me, you know, and that sort of thing. And, like, life can be easy for you.

Todd Melby: Why did you put the liquor store scene in the movie?

Charles Burnett: That liquor store is round the corner from my house and it was sort of like a meeting place, a watering hole. You know, you would always go to the liquor store for some reason. You know, it was I mean, they had supermarkets, but I think I'd been buying more things at the liquor store than I did any place else. I could just buy it. Not everything. No fruits or anything like that. But, you know, milk, sugar, they had things that you just needed. It was so much a part of the reality of the neighborhood. They had liquor stores in almost every corner, you know. So you don’t have to walk too far to get to one, you know.

Todd Melby: Right. Which makes sense for putting it in the movie. Well, Charles Burnett, thank you so much.

Charles Burnett: Thank you.